The art of the trial smile in cosmetic dentistry

We cannot underestimate the value that a beautiful smile can bring to the wellbeing of our patients.1 Numerous subjective studies claim that individuals hate showing their teeth in photos, and even more upsettingly, that their smile is holding back their life. It is therefore a monumental moment when a patient eventually builds up the courage to see their trusted dentist with hopes of improving their teeth.

Comprehensive consultations with highly-trained cosmetic dentists typically involve a thorough dental and aesthetic examination. From this, discussions are had surrounding various management options and potential digital outcomes, however, there are still the lingering doubts for patients regarding how their final smile will appear and how it will function. This is where a “trial smile” proves to be an invaluable tool.

What is a trial smile?

Weighing up patient desires, dental expertise and testing for functionality are the essential purposes of a trial smile.1 This works for patients wishing to undergo porcelain veneer treatment, as well as those seeking composite resin build-ups and composite veneers. Essentially, any treatment which alters the size, proportions and shape of teeth within the aesthetic zone warrants a trial.2

The opportunity for a patient to assess in real time within their own mouth a trial of the final result, cannot be undervalued. They can see proportions of the teeth, colour and shape, all within the framework of their lips and face. This is akin to a conversation between the dentist and patient, addressing expectations, hopes and desires.

It must be remembered that failure of treatment is not only the result of technical problems, but also from poor communication. A “mock-up” enables us a greater control over the end result and definitely mitigates issues related to repeat debonding, discomfort, and fracture of restorations. It also allows the opportunity to perform minimally-invasive tooth preparation, with the overall aim of creating a beautiful smile and a confident patient.3,4

In this article, we plan to explore the different methods of designing and producing a trial smile.

Lab made wax-up

This is the classic technique most cosmetic dentists tend to rely upon when producing a trial smile. It begins by collating the information obtained from the patient regarding their desired aesthetics.2 Size, shape, proportions and colour are all discussed. Subsequently, photographs are sent to the technician with the aim of balancing dental outcomes with overall face cosmesis (please refer to the smile design article in the May 2020 issue of AM for the key principles).

The technician also requests an impression of the patient’s teeth and a study cast is created in the laboratory. The technician produces a diagnostic wax-up – a threedimensional project in wax. This forms the basis of the mock-up. 3-5

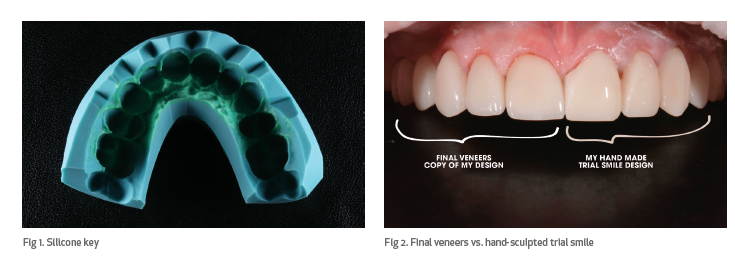

From the wax-up, a silicone key can be made (figure 1). This serves as a reverse mock-up, to which temporary material, typically bisacryl resin, is placed inside. The silicone key is seated in the mouth over the teeth to produce the trial smile.

There are multiple names given to this technique including Mock-Up, Bonded Functional Esthetic Prototype (BFEP) and Aesthetic Pre-Evaluative Temporaries (APT).2,3 Some dentists utilise the Gurel technique when planning and preparing the teeth for porcelain veneer work. This is where the mock-up is placed in the patient’s mouth, serving as both the foundation for temporary veneers and also as a guide for the dentist through which they can prepare the teeth.

Essentially, the dentist prepares the teeth for veneers through the mock-up in order to ensure consistent and optimal preparation. The idea is that the clinician has direct intra-oral guidance to avoid over-preparation of tooth structures, ultimately minimising tooth reduction.6,7

Following preparation, the dentist can use the same silicone key to produce temporary veneers. This is the moment which allows the patient to trial the smile and make changes to the prototype.6,7

The free-hand technique

This technique is gaining popularity worldwide, with dentists attracted to the ability to fully control the shape and final design of the teeth. Despite this, there is very little literature surrounding this as it is a method born out of vision and creativity, often by individual cosmetic dentists, of which there are very few who use this technique.

Instead of relaying the information to a laboratory technician to build a trial smile, the clinician takes ownership over the production.This allows them to create an entirely bespoke blueprint for the execution of each individual case Our personal opinions surrounding this is that it is a revolutionary technique. Though simple conceptually, the execution requires technical expertise, a thorough understanding of dental aesthetics and the balance of such things within the overall face. The idea is to use the patient’s initial situation as the template upon which to build the trial smile directly.5

Logistically, there are admittedly difficulties when requesting a lab wax-up, coupled with the conversion of that intra-orally, especially if this is the basis upon which patients make a final decision. The free-hand smile is a fantastic way, at the consultation appointment, to immediately see the planned design of the new teeth, in real time, against their own lips and face. This is a highly technique-sensitive method and relies on a very highly-trained and visionary cosmetic dentist.

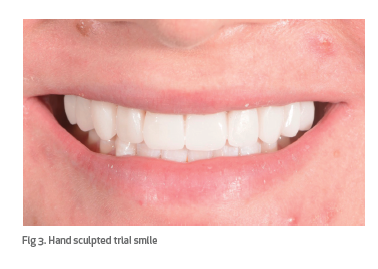

This technique puts the dentist in control of the aesthetics, however requires the dentist to create each individual tooth shape, using resin materials. This would create a critical communication tool when designing the final aesthetics (figure 2).

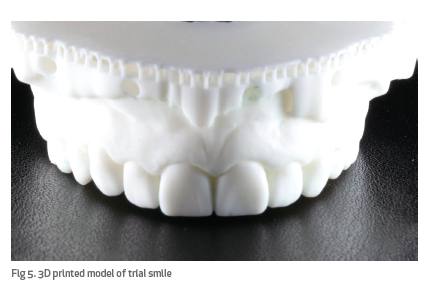

Before beginning any procedure, flowable composite is directly applied to the teeth that are to be altered. If the teeth are to be made shorter, this can be blocked out with a black marker pen, and should the gum be raised, the flowable comp can be placed over the gum (for the sake of visualisation). This requires the clinician to be skilled in layering the flowable composite, as well as understanding dentitionn in terms of position; and primary, secondary and even tertiary anatomy, to ensure lifelike texture (figure 3).

The entire design can be created during a single appointment fully controlled by the dentist, with hopes of marrying up tooth and facial proportions. Following this, an impression or a digital scan is done, along with photographs, and in some cases video recordings.

Additional information such as lengths and widths of the teeth and drawings may also be sent. The impression or scan serves as the negative by which the provisional veneers are made. The hope is to eliminate the need for any laboratory guesswork and ensure the clinician, who understands both technical options and patient desires, has total control.

With time given to the patient, and their approval sought prior to the fabrication of the final porcelain veneers, this technique allows a true visualisation, and manages patient expectation greatly (figure 4).5

Digital trial smile

Over the last few decades there has been the evolution and improvement of digital technology flooding every aspect of the modern world. Therefore, it must come as no shock that when discussing trial smiles, digital dentistry holds a prominent place.

Programmes such as Adobe Photoshop and DigitalSmileDesign (DSD) in particular serve as great tools in designing the shape and form of dentition.8 Through the use of intra-oral scanners, we can accurately capture anatomical variations. Coupling this with good photography allows the patient’s face to be digitally processed and added to formulate an overall design.1 The patient eventually sees a digital portrait of their new smile.1,8

Similar to the free-hand technique, this process can occur during the consultation phase, which allows a more open and inclusive conversation surrounding desired outcomes. From that point, the workflow can be entirely digital, with the design printed into a threedimensional model to be used in making the provisional restorations (figure 5).1

Benefits of the trial smile

With proper execution, the trial smile elevates from a beneficial tool to a fundamental necessity. It allows the patient an accurate visualisation of the desired end result, improving communication, motivation and consultation processes.

Remember that communication is the essential tool when obtaining informed consent, and poor communication leads to failures in treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. Using a lab mock-up, digital smile or the direct free-hand technique enables us to control the direction without even beginning the work. If anything, the management of patient expectations and the use of direct visuals form invaluable tools in the journey to a confident smile.

Conclusion

Interestingly, within our own experience, there are still many dentists who have not embarked upon the use of a trial smile. In our opinion, this is not a discussion of whether to do or not, but rather how to best perform. Each technique can work better or worse depending on the experience of the clinician, but we believe dentists must attempt or experience each to eventually decide upon their methodof choice.

REFERENCES

1. Garcia PP et al. Digital Smile Design and Mock-up Technique for Esthetic Treatment Planning with Porcelain Laminate Veneers. J Conserv Dent. 2018 Jul-Aug;21(4):455-458.

2. Gurrea J, Bruguera A. Wax-up and Mock-up. A Guide for Anterior Periodontal and Restorartive Treatments. Int Esthet Dent. Summer 2014;9(2):146-62.

3. Dragusha, R., Ibraimi, D. Mock-up: An Aid in Different Steps in Aesthetic Dental Treatment. European Scientific Journal, ESJ. 2016 Mar;12(6):290

4. Magne P, Magne M. Use of Additibe waxup and Direct Intraoral Mock-up for Enamel Preservation with Procelain Laminate Veneers. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2006 Apr;1(1):10-9.

5. Furuse AY et al. Planning Extensive Esthetic Restorations for Amnterior Teeth: Use of Wax-up Study Casts and Composite Resin Mock-ups. Gen Dent. 2006 Jan-Feb;64(1):e6-9.

6. Gurel G, Morimoto S, Calamita MA, Coachman C, Sesma N. Clinical Performance of Porcelain Laminate Veneers: Outcomes of the Aesthetic Pre- Evaluative Temporary (APT) Technique. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012 Dec;32(6):625-35.

7. Porcelain Laminate Veneers: Minimal Tooth Preparation by Deisgn. Gurel G. Dent Clin N Am. 2007 Apr;51(2):429-31.

8. McLAren EA, Goldstein RE. The Photoshop Smile Design Technique. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018 May;39(5):e17-e20.

Dr Yasmin Shakarchy completed her dentistry training at the University of Birmingham. She is a Member of the Faculty of Dental Surgery (MFDS Ed) and holds a a PG certificate in aesthetic and restorative dentistry. She won Best Young Dentist at the 2018 Dentistry Awards. Instagram: @doctor_yasmin_

Dr Sam Jethwa is the founder of Bespoke Smile Academy, providing hands-on education on indirect restorations to dentists. He is director of communications at The British Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry and was the winner of the Fast Track 4 award in 2017 and Dentex Clinician of the year 2020.